Why are history majors successful in military careers?

Leaders across the centuries have consistently emphasized the role that historical study plays in achieving military success. Napoleon noted that “The principles of war are those which have directed the great commanders whose great deeds have been handed down to us by history. . . . [Studying history] is the only way of becoming a great captain and to obtain the secrets of the art of war.” General George S. Patton once stated flatly that “To be a successful soldier you must know history.” And more recently, in the video below, retired Marine Corps general and former U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis credited his reading of history for his keen ability to make good decisions. Why do those who study history tend to do well in military careers?

“. . . those charged with managing the preparations for war must understand our national objectives and their operating environment, and essentially these are the products of history. Thus, for the military leaders, the study of history becomes a professional necessity; the neglect of this study in American services creates a professional shortcoming.”

—William E. Simons, “The Study of History and the Military Leader”

“[History] is inherently broader, deeper, and more diverse than the study of any other area of human activity. It encompasses every aspect of the experience of humanity, and it tends to broaden the vision and deepen the insights of its readers. Events are seen as part of a much broader framework filled out with complex and dynamic interrelationships of social forces, individuals, location, and timing. . . . History gives its readers a consciousness of particular circumstances in human affairs. It teaches them to be wary of broad generalizations and quick solutions. . . . A study of past wars is fundamental to preparation for the next war, for current military problems cannot be solved without an understanding of the past from which they stem.”

—Milan Vego, “Military History and the Study of Operational Art,” JFQ

“. . . theorists agreed that waging war successfully was more art than science, and that combining war-gaming with the study of history was essential to understanding it. The immediate, wide-ranging influence of their ideas ensured that the study of war would have a long affinity with games.”

—Cynthia J. Miller and A. Bowdoin Van Riper, Horrors of War: The Undead on the Battlefield

“On 6 June 1944, as the allied forces began the invasion of Normandy, General George S. Patton, Jr., wrote to his son, then a cadet at the United States Military Academy, that ‘to be a successful soldier, you must know history.’ The number of similar pronouncements from noted military figures, including Napoleon, is almost endless and the basic refrain is the same—to understand the present and to prepare for the future the study of history is vital. . . . . As Marshal Foch wrote, ‘no study is possible on the battlefield, one does simply what one can in order to apply what one knows.’ Despite vast changes in technology since World War II, the combat leader may still learn much from the study of past battles and campaigns. Weather, terrain, and intelligence of friendly and enemy dispositions, for instance, are as important today as in the days of Alexander, Frederick the Great, and Napoleon: human reactions in combat remain relatively constant.”

—John E. Jessup, A Guide to the Study and Use of Military History

“The importance of the study of history for the military leader results from the uniqueness of the historical discipline, a uniqueness which can be examined in two dimensions. First, the study of history demands an intellectual process somewhat different from those employed in other disciplines and especially useful to the military officer. Second, history deals with subject matter upon which many other valuable fields of study depend for the accuracy of their assertions.”

—William E. Simons, “The Study of History and the Military Leader”

“Unlike the sciences, both physical and social, history deals with particulars rather than universals. Despite formulation of a few ‘theories’ of history, it is concerned with the causes and effects of individual events, not with developing and testing hypotheses to predict the outcomes of all similar events. As a result, history deals with life as the evidence shows it to have occurred, not with idealized conceptions or with artificially categorized segments of life. These characteristics make history especially valuable for the military officer. Essentially, the officer is a solver of everyday problems. [The officer] is concerned with specific situations, e.g., the problem of improving maintenance in a particular bomb wing, the development of an operations plan for a particular amphibious assault, or the problem of maintaining high morale in a particular isolated situation. To accomplish takes such as these he must examine the situations in their entirety, taking into consideration all related factors. [The officer] usually cannot isolate and test individual factors, as in a laboratory. Rather [a military officer] must perform like a discriminating clinical observer who has learned to recognize cause and effect relationships and to make connections between related circumstances in the most complex situations.”

—William E. Simons, “The Study of History and the Military Leader”

“The study of history, enabled by professional instruction and civilian education, will increase Army special operations’ regional expertise and enhance intellectual creativity to assist in addressing complex problems, driving the operations process and developing sound strategic options. Army special operations forces work in a complex and uncertain environment. . . . Understanding the history within a particular environment is critical to these nuanced shaping operations and ARSOF can only arrive at this understanding through an intellectual maturity honed by the study of history. . . . ARSOF expect to achieve effects of magnitude disproportionate to their small footprint. The ability to think historically assists in achieving these effects and is necessary for success at the strategic, operation and tactical levels of war.”

—Lt. Col. Heath Harrower, “Effectiveness Through Historical Consciousness,” Special Warfare

“. . . Historical knowledge is an essential element that enables the operations process and ‘buys down’ risk by providing a more complete understanding, thus enhancing the odds for success through a sound and thorough operations process that reduces the effects normally attributed to such elements as fate, unforeseen circumstances, luck, fog, and friction. Using history as a stand-in for experience, commanders and their staffs can objectively evaluate courses of action in light of their alternatives and thus offer sound solutions based on more than a contemporary (and incomplete) understanding of the operational environment. The ability to think in a historical context is also critical to strategic success because the clarity and predictability derived from a mastery of doctrine and the operations process does not automatically translate into strategic competence. Success at the tactical and operational level, however brilliant, may not translate into strategic success . . . Accordingly, historical knowledge is a critical factor in developing, managing, and adapting sound strategic options. . . . The concerted study of history is essential to understanding the environment and will increase Army special operations’ regional expertise and enhance intellectual creativity to assist in addressing complex problems, driving the operations process, and developing sound strategic options. Admittedly, studying the past is not a surefire method for predicting the future; however, it does greatly prepare us for the future by expanding experience and increasing wisdom, and thus bettering our judgment.”

—Lt. Col. Heath Harrower, “Effectiveness Through Historical Consciousness,” Special Warfare

“The study of history for the military professional is time well spent to hone individual and institutional skills. Understanding lessons learned and the continued development of the lesson will provide current and future leaders a firm foundation in choosing courses of action when confronted with a challenge. . . . as leaders and professionals we need to do everything we can to learn Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) from the leaders of the past . . . We benefit from studying history by looking at what was supposed to happen, what actually did happen, and how we can improve in the future when performing similar missions. Studying and learning to use examples from prior experiences allows us to continually improve on the successes of our past and also to correct the failures of our past so they don’t ever happen again.”

—Kevin Theismann, “Why is it Important to Study History?”

“It is of vital importance that the military leader be versed in the study of military history. By studying history, the military leader uses critical thinking, grounded in military history, as the basis for operational decision making. Military history provides the leader with an understanding of military concepts, the evolution of war-fighting doctrine, supplies an understanding of leadership actions, provides the tools to learn from past experiences, and while broadening one’s knowledge of military subjects. Military history is the Army’s institutional past and provides the patterns, trends, and relationships necessary for the development of current and future war-fighting doctrine. . . . Military history provides a means of looking to the past in order to look to the future. . . . the study of military history is a vital piece of a military leader’s education in the profession of arms. It provides the leader with a view of past operations so he or she may not repeat past mistakes; it broadens one’s tactical knowledge and provides a picture of the past to help shape future doctrine. The United States Army, in understanding the importance of military history, has incorporated history in all aspects of its training.. . . . The Army focuses on three domains of training: operational, institutional, and, self-development. All three domains are steeped in military history. Current operations are conducted through lessons learned from the past and from theory. Institutional learning uses history to teach today’s leaders how to perform effectively through the study of past leadership actions. Lastly, the military leader is encouraged to study military history as a means of self-development. . . . when studying theory, a military leader imagines how using a specific tactic or strategy might have a predicted impact on the battlefield. . . . For the military leader, the importance of history cannot be understated. By studying history, the military leader uses it as the basis for operational decision making. Military history provides the leader with an understanding of military concepts, war fighting doctrine, leadership decision in action, and provides an instrument to learn from past experiences to direct current and future military operations.”

—Jason B. Caswell, “History and the Military Leader”

General Duane H. Cassidy: “I have no more original thought than the next guy. I am not terribly cerebral. There are a lot of people who have a lot more intelligence than I do. I am not putting myself down. I’m just trying to assess myself. So my successes have come from having good instincts and a keen eye for knowing where to get good information and good advice to make up for my own weaknesses. Go to the history books. It is there. There is very little we do that hasn’t been done before in some sense . . Leaders need to study history and seek out historians who are as excited about history as you two are, to learn how history lessons can be applied. So I’ve drawn extensively upon the lessons of history and my historians.”

—Duane H. Cassidy, James K. Matthews, and Margaret J. Nigra, General Duane H. Cassidy, Commander in Chief

“Perspective gives a sense of proportion in relation to time, place, and circumstances. It persuades a person to look at the long view over short-term advantages and disadvantages, and in war to recognize that the ultimate objective must prevail over intermediate objectives. Perspective temporizes excessive optimism and pessimism by developing an awareness of continuous change. And it helps develop a sense of values for the critical appraisal of achievements, methods, and decisions. . . . the study of history develops a great reservoir of experience. Few question the value of an experienced officer in any position. . . . Yet few appreciate the value of history as an extension of general experience. Through the study of history it is possible for an officer to gain at least a part of the experience of an officer in the Civil War, in World War I, in World War II, and Korea. Experience is the raw material of imagination, and history is the great source of experience. Far from discouraging new methods and new ideas, history is the very basis for them. There is no such thing as abstract imagination. Imagination is a reorganization of elements out of past experience. With no experience at all there could be no imagination at all. The value of the ‘lessons of history’ is in providing those elements out of experience. They should be used then as elements of imagination for meeting new situations, not as patent solutions for situations which cannot fit exactly. . . . . experience is the raw material, and history is the great source of experience. When one speaks of a very wise man, he usually thinks of an old man. Why? It is not because age brings wisdom, but because the older man is likely to have had more experience. . . In any military organization nothing can be more valuable than good ideas and right decisions. No officer should be more sought after as a miliary asset than the imaginative and wise officer. Both imagination and wisdom are the products of experience—with the benefit of intelligence and ingenuity. And there is no better way for extending experience vicariously than by the study of history.”

—James Huston, “The Uses of History,” Military Review

“Studying history allowed a leader to understand what normally occurred in a given situation. In real-world circumstances this knowledge heightened the leader’s ability to see and analyze all potential courses of action. Leaders should also recognize that no event completely reflects the normal: Every circumstance has unique attributes. The most effective leaders identified these attributes and then exploited departures from the normal.”

—Kevin D. McCranie, Mahan, Corbett, and the Foundations of Naval Strategic Thought

“. . . the study of history develops critical problem-solving skills. According to the historian Allan Nevins, the nature of historical inquiry involves ‘an attempt to find the correct answer to equations which have been half-erased.’ This description should sound familiar to anyone who has dealt with the ‘fog of war.’ . . . The critical reasoning skills intrinsic to historical inquiry are vital to the multifaceted problem-solving demanded of military leaders, even those who have absolutely no interest in history. For this reason alone, military history must be a fundamental component of a military education.”

—Cpt. Mark Ehlers, U.S. Army, Armor

“One of the key prerequisites for applying operational art is full knowledge and understanding of its theory, and theory cannot be properly developed without mastery of military history. The great military commanders were, almost without exception, avid readers of history. Because the opportunities to acquire direct experience in combat are few for any commander, the only sources of such knowledge and understanding are indirect, and military history is the most important source of such experience. . . . Planning games and wargames, field trips, and exercises are excellent tools for improving the quality of operational and tactical training. However, only the study of military history can provide insights into all aspects of warfare. . . . A proper study of military history helps to derive general principles of leadership through a critical reading of the biographies and memoirs of the great captains of the past. It also helps in understanding the reasons for their successes and failures. By studying military history, we can get a sense of the pressure and responsibility of commanders in uncertain situations when critical decisions must be made.

—Milan Vego, “Military History and the Study of Operational Art,” JFQ

“History is very exciting and a great motivator. History is a motivator personally because, in an arrogant way, I want to go down in history . . . I want to be known as somebody who did something really important . . . . Also, history provides people with a reason for being. It provides legitimacy. It provides a powerful pride and positiveness deep inside you. History provides that because in our business we create history. Perhaps most importantly, studying history can help a leader prepare for the future. The past provides you an atmosphere of clear thought so you can then attempt to influence the future. That is all we are trying to do as leaders, influence events.”

—Duane H. Cassidy, James K. Matthews, Margaret J. Nigra, General Duane H. Cassidy, Commander in Chief

“Military history is also quite useful in instilling desirable values to the young men and women in the military . . . historical narrative is replete with the stories of men and women of all ranks, colors and creeds who exemplify either these values or their obverse. Using the historical narrative elevates these values out of the realm of the abstract to reality. Just as the demonstrations of the principles of war show, these are real human beings reacting to real situations in real ways with real consequences. . . . Knowing how men and women reacted in similar situations throughout history brings either a comfort or a warning to those faced with similar dilemmas today, and it is vital to imparting the values that make up a complete military education. . . . At its core, history is a supremely humanistic discipline—it is about people. Military history brings life to abstract principles of war. . . . It puts forth flesh-and-blood examples to impart values the military demands of its members. It teaches the critical reasoning skills needed to succeed in military leadership. There is no question that military history must be part of the military-education curriculum if we expect to produce leaders of the caliber required to win our nation’s wars.”

—Cpt. Mark Ehlers, U.S. Army, Armor

“Another important value of history is inspiration. Unquestionably, the obstacles and hardships of warfare are magnified by mental responses. . . . Probably a more direct inspirational value of military history is in the building of esprit de corps. Some of the old regiments long have given this serious attention, and in recent years a great deal more has been done in the way of developing the inspiration value of unit history, and of the history of the Army as a whole.”

— James Huston, “The Uses of History,” Military Review

“The history major helps cadets understand the world and its problems by studying the ideas and forces of the past that have shaped the present. The knowledge gained and the perspective developed are important to the education of the professional Air Force officer and are particularly valuable for cadets considering careers in operations, plans, attaché duty, and intelligence. Because the major emphasizes the development of critical thinking, research techniques, and writing skills, it is excellent management and leadership training for junior officers aspiring to future staff and command positions.”

—United States Air Force Academy, Curriculum Handbook with General Information

“Experience abundantly shows the critical role and importance of comprehensive understanding and knowledge of military history for all officers, and especially for those who aspire to or are selected to take the highest duties in their respective Services. Almost without exception, successful operational commanders have been serious students of history. Because the life of any officer is too short, the opportunities for acquiring operational perspective by commanding large forces in combat are rare indeed. Yet the broad view and solid knowledge and understanding of the art of war must be obtained in peacetime. It is too late to obtain that knowledge once the hostilities start. . . . The most important and proven source of that indirect experience is military history. A future operational commander should approach the study of military history systematically and as a lifelong effort; otherwise the results will be wanting.”

—Milan Vego, “Military History and the Study of Operational Art,” Joint Force Quarterly: JFQ

“The history major helps one understand the world and its problems by studying the ideas and forces of the past that have shaped the present. Moreover, history is eminently practical in this world of incessant and often dramatic change. Understanding and coping with change will be one of this country’s greatest challenges . . . .”

—United States Air Force Academy, Academic Majors Handbook with General Information

“The study of military history will enable these leaders to develop a far-fighting perspective even though they may not have actually participated in warfare. In fact, Rear Admiral (Retired) Henry E. Eccles believes the best way to achieve experience is through actual combat; however, if this is not possible, the next alternative is through the study of history. In his view, ‘. . . of the continuing patterns of thought and behavior revealed by the study of history is essential’ for those who presently or will exercise authority. . . The rapidly changing technology of modern warfare requires adaptability, flexibility, and innovation from military leaders. History serves as a valuable aid to leaders when they are evaluating ideas and creating new methods to meet new situations.”

—Capt. Charles G. Carpenter and Capt. Stanley J. Collins, Air Force Journal of Logistics

“As a laboratory of experience, history represents a broad foundation which can be drawn upon not only by other social sciences but also for individual education and training in the practice of an art or profession, as in the case of the military for whom vicarious experience is important. The study of history develops a sense of perspective, of the continuities and discontinuities, and of time in human affairs. A.L. Rowse has put it well: ‘Not to have a sense of time is like having no ear or sense of beauty—it is to be bereft of a faculty.’”

—John E. Jessup, A Guide to the Study and Use of Military History

“Army special operations personnel that possess an ability to think in a historical context can distill history into lessons that assist in making decisions and planning for the future. Dates, names and locations serve well in Trivial Pursuit, but the ability to think in a historical context goes well beyond a simple compilation of facts. In his book Balkan Ghosts, Robert Kaplan provides an example of this ability when describing an elderly gentleman in Yugoslavia whom he characterized as ‘able to predict the future.’ This gentleman paid no attention to daily headlines because the ‘present for him was merely a stage of the past moving quickly into the future’ and instead he thought in purely historical terms. The ability to distill and understand the past allowed him to predict correctly trends in governance to include economics, leadership and reforms. While this is an extreme example and we should not expect an ability to predict the future, understanding past events and leveraging that understanding as experience certainly lends depth to regional expertise. Additionally, leaders who learn through others’ experience will possess knowledge that may allow them to conceptualize faster than the enemy can adapt, critically important when the consequence of failure and incompetence are so final. Somebody, somewhere, at some point in time experienced the same events Army special operations will face in the future. Man has waged war over thousands of years, providing plenty of experience to leverage outside of one’s own, and through concerted study Army special operations personnel can identify lessons applicable to the situations they will face. The ability to distill the lessons of history to the degree that Army special operations personnel can ‘anticipate [these] changes in the operational environment and exploit fleeting opportunities’ and use them to assist linking tactical success to strategic success, like any other task, requires proficiency acquired through education and instruction. . . . Historian John Lewis Gaddis compares achieving this proficiency to that of achieving proficiency within sports. Proficiency in sports requires knowledge of the rules and a practice of baseline skills that provides preparation for general circumstances. However, each game contains its own characteristics and room is needed for individual discretion and judgment to address the particular circumstances. . . . This understanding also allows commanders to better connect all elements of the environment to drive the operational process through a more comprehensive approach. Critical to understanding is establishing context, that is, the set of circumstances surrounding the event or situation. History serves as the basis for this context and historical thought allows for a better visualization of a desired end state by enabling a broader understanding of the environment. This is especially important when dealing with complex and unfamiliar problems that commanders and their staffs cannot readily frame within existing doctrine.”

—Lt. Col. Heath Harrower, “Effectiveness Through Historical Consciousness,” Special Warfare

“Now, as in previous times of change, asking critical, creative, contextual questions is essential. Historical education creates higher-order thinkers who can develop and implement policy and link ends, ways, and means. We can and should have leaders with historical understanding at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels of war. The study of history creates wisdom and perspective, helps leaders to cope with ambiguity and uncertainty, and sharpens critical thinking skills. In a word, history educates. Study of history makes us a smarter, and therefore better, Army. General Martin E. Dempsey, former chief of staff of the Army and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, makes the point constantly that historical knowledge is an essential part of strategic thinking and leadership at all levels.”

—Charles R. Bowery, Jr., “The Chief’s Corner,” Army History: The Professional Bulletin of Army History

“History is the only database available to assist in the understanding needed to successfully deal with current and future problems. As Army special operations continue to assess changes to doctrine, organization, training, material, leadership and education, personnel and facilities, continued investment in people and ideas remain essential, more so than investment in platforms. Within this, resources dedicated to enabling historical thought will set the foundation for the enduring situational understanding expected of Army special operations personnel.”

— Lt. Col. Heath Harrower, “Effectiveness Through Historical Consciousness,” Special Warfare

Notable military and intelligence professionals who majored in history

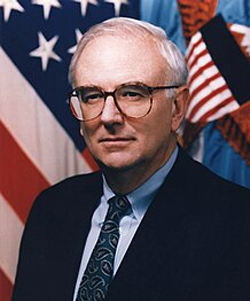

Les Aspin, former U.S. Secretary of Defense

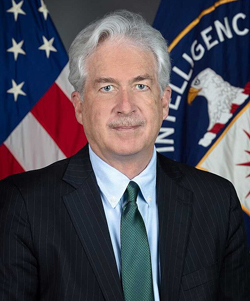

William J. Burns, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

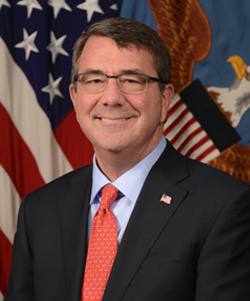

Ash Carter, former U.S. Secretary of Defense

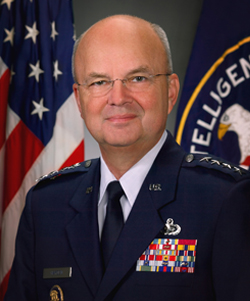

Michael Hayden, former Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

John Kirby, retired Rear Admiral; Coordinator, Strategic Communications, NSC

James Mattis, retired USMC general; former U.S. Secretary of Defense

Carol M. Pottenger, retired USN Admiral; first woman to command major combat organization

Angela Salinas, retired USMC General; first female commander, USMC recruitment

Louise Currie Wilmot, retired USN Rear Admiral; first woman to command a USN base

Others

David Axe, military correspondent, blogger, War Is Boring

Tim Barrett, former Chief of Navy, Royal Australian Navy

Eytan Ben-David, Acting National Security Advisor, Israel

Henri Bentégeat, former Chief of the French Defence Staff; former chair, EU Military Committe

Scott D. Berrier, retired US Army Lt. General; former Director, Defense Intelligence Agency

William C. Bilo, retired US Army General; former Deputy Director, Army National Guard

Richard M. Bissell, CIA officer responsible for Bay of Pigs and U-2 incident

Dan Biton, Israeli general, Head of the Technological and Logistics Directorate

Heber Blankenhorn, pioneer of military psy-ops

H. Steven Blum, retired US Army general; former Chief of the National Guard Bureau

John P. Bobo, Medal of Honor recipient

Vincent E. Boles, retired US Army General; Chief of Ordinance; Commandant of Aberdeen PG

Fred Borch, chief prosecutor of the Guantanamo commissions

Bryan D. Brown, retired Army General; former commander, U.S. Special Operations Command

John S. Brown, US Army General; former Chief of Military History of the US Army

Clare Cameron, UK Director of Defence Innovation, Ministry of Defence

Charles C. Campbell, retired Army General; former Commander, US Army Forces Command

Frank Castellano, commanding officer, Center for Surface Combat Systems

William C. Chase, US Army General, instrumental in post-WW II occupation of Japan

Robert T. Clark, retired US Army General; former Commander, Fifth Army

Ezra Cohen, former Acting Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence

R. Clarke Cooper, former Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs

William E. Cooper, former Deputy Director for Foreign Intelligence at DIA

William W. Crouch, US Army General, Vice Chief of Staff, U.S. Army

John Cusick, retired US Army General; former Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army

Daniel A. Dailey, former Sergeant Major of the Army

Richard Dearlove, former head of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6)

John M. Deutch, former U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense; former Director, Central Intelligence

Walter Doran, former commander-in-chief, US Pacific Fleet

Eric S. Edelman, former Undersecretary of Defense for Policy

Dawn Eilenberger, Deputy Director of National Intelligence

Leon F. Ellis, retired USAF colonel; Vietnam POW

Richard H. Ellis, USAF General, former Commander-in-Chief, Strategic Air Command

George Elsey, naval commander, advisor to FDR and Truman

Stephen E. Farmen, retired US Army General; cmdr., US Army Military Surface Deployment

Roy K. Flint, retired US Army General; former Dean of the Academic Board, USMA

James L. Fowler, founder of the Marine Corps Marathon

Carl H. Freeman, retired Army General; former Chair of the Inter-American Defense Board

Terry Gabreski, retired USAF General; former Vice Commander, Air Force Materiel Command

Shlomo Gazit, Israeli Major General; Head of Military Intelligence Directorate

Bradley Gericke, Deputy Director of Strategy, Plans, and Policy, US Army

Carey Gordon, USAID Chair, National Defense University

William E. Gortney, retired USN Admiral; Commander,. U.S. Northern Command

Kendall Gott, Senior Historian at the US Army Combat Studies Initiative

Terrence C. Graves, Medal of Honor recipient

David Hackworth, youngest U.S. Army colonel in Vietnam

Terry Halvorsen, former Chief Information Officer, U.S. Department of Defense

John W. Handy, retired USAF General

William Hardin Harrison, retired US Army General; former commander, Fort Lewis

Syed Ata Hasnain, former Secretary of the Indian Army

Roberta L. Hazard, retired USN Rear Admiral; first female commander, U.S. Naval Training

John W. Hendrix, Commander, U.S. Army Forces Command

Kathleen Hicks, first woman to serve as Deputy U.S. Secretary of Defense

William W. Holloman, Army officer, member of Tuskegee Airmen

James M. Holmes, retired USAF General; former Commander, Air Combat Command

Gregory C. Huffman, USN Rear Admiral; Commander, Carrier Strike Group 12

William G. Hyland, Deputy National Security Advisor to Ford; editor, Foreign Affairs

William Inboden, Executive Director, Clements Center for National Security, UT Austin

Bobby Ray Inman, retired USN Admiral; former National Security Agency Director

Galen B. Jackman, retired US Army General; former Chief Legislative Liaison for the U.S. Army

Charles H. Jacoby, retired Army General; former Commander, U.S. Northern Command

John D. Johnson, retired US Army General; Director, Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat

Nick Justice, US Army General; former cmdr., US Army Research, Development

William F. Kernan, retired US Army General; former CIC, Joint Forces Command

Samir El-Khadem, former Commander, Lebanese Naval Forces

John Kimmons, retired US Army General; former Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence

Gregory C. Knight, US Army General; Adjutant General of Vermont

David Ledson, Chief of Navy of New Zealand

Rudy de Leon, Deputy U.S. Secretary of Defense

R. Jay Lloyd, former Master Chief Petty Office of the Coast Guard

Guido Manini Rios, former Commander-in-Chief of the Uruguay National Army

Mary McCarthy, former CIA Inspector General

Terry McCreary, USN Admiral; former Chief of Naval Information

Frank McKenzie, former Commander of Central Command

David D. McKiernan, U.S. Army General; former commander, U.S. forces in Afghanistan

Brendan McLane, USN Rear Admiral; Commander, Naval Surface Forces Atlantic

Om Prakash Mehra, former Chief of the Air Staff, Indian Air Force

Paul T. Mikolashek, retired US Army General; former Inspector General of the Army

Christopher C. Miller, former Acting U.S. Secretary of Defense

Han Min-goo, former South Korean Minister of Defense

Thomas S. Moorman, Jr., former Vice Chief of Staff, USAF

Thomas R. Morgan, retired USMC General; former Asst. Commandant of Marine Corps

Leah Mosher, one of the first three women to earn wings in Canadian Air Force

John F. Mulholland, Jr., retired US Army general; former Assoc. Dir., Military Affairs, CIA

Arturo Muñoz, CIA senior intelligence officer

Robert B. Murrett, USN Vice Admiral, Director of National Geospatial Intelligence

Richard F. Natonski, retired USMC General; Commander, USMC Forces Command

Yair Naveh, Israeli major general, former Deputy Chief of the General Staff

Richard I. Neal, retired USMC General; former Assistant USMC Commandant

Robert Neller, retired USMC General; former Commandant of the Marine Corps

Dave Richard Palmer, retired US Army General; former Superintendent of the USMA

Steve Parode, Rear Admiral, USN; former Director, Warfare Integration Directorate

Jocelyn Paul, Commander of the Canadian Army and Chief of the Army Staff

Michael Pillsbury, Director of the Center on Chinese Strategy, Hudson Institute

Jayant Prasad, former Director General, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses

Klaus Reinhardt, German general; Commander, German Army Forces Command

Robertus Remkes, Director, Strategy, Policy and Assessments, U.S. European Command

Ronald G. Richard, retired USMC General; former commander, Base Camp Lejeune

Robert W. RisCassi, retired US Army General; former Vice Chief of Staff; CIC UN Command

Anthony J. Rock, USAF General; Inspector General of the U.S. Air Force

Wayne Rollings, former commanding general, USMC

Yael Rom, among first female Israeli air force pilots

Ann E. Rondeau, retired USN Vice Admiral; President of the Naval Postgraduate School

Alan Sabrosky, former Director of Studies at U.S. Army War College

B. Chance Saltzman, U.S. Space Force general and Chief of Space Operations

Kevin Sandkuhler, retired USMC General

Vigen Sargsyan, former Armenian Defence Minister

Robert H. Scales, retired US Army General; former commandant, U.S. Army War College

Michael Scheuer, former officer, CIA

Ty Seidule, retired US Army General; former head, USMA History Department

Vladimir Semichastny, former Chairman of the KGB

Kalev Sepp, counterinsurgency and counterterrorism expert

Prabhu Ram Sharma, Chief of the Army Staff of the Nepalese Army

John Sherman, CIO of the Department of Defense

Shawn Skelly, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Readiness

Stephen Sklenka, USMC General; Deputy Commander, Indo-Pacific Command

Hans Speidel, first full general in West Germany; principal founder, Bundeswehr

Vincent Stewart, Lt. General, USMC, Deputy Commander at U.S. Cyber Command, DIA

William O. Studeman, retired USN Rear Admiral; former acting Director of the CIA

Jack C. Stultz, retired U.S. Army General; former Commanding General, US Army Reserve

Gordon R. Sullivan, former Chief of Staff of the Army and former Acting Secretary of the Army

Allan Taylor, former Director-General of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service

James D. Thurman, retired Army General; former Commander, U.S. Forces Korea

Eugene F. Tighe, former Director of U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency

Matt Urban, one of the most decorated army soldiers of all time

Archie Van Winkle, Medal of Honor recipient

Alexander Vindman, retired US Army Lt. Colonel; former Director, European Affairs, NSC

Ricky L. Waddell, retired US Army; former Deputy NSA; former Assistant to CJCS

Nick Warner, Director-General of the Office of National Intelligence, Australia

Hans Wegmueller, former head of the Swiss Intelligence agencies

R. Steve Whitcomb, retired US Army General

Robert P. White, retired US Army General; former commander, Fort Hood, Texas

Brian E. Winski, former commander of 101st Airborne Division

Frederick F. Woerner, Jr., US Army General; former CIC, US Southern Command

Alan Wood, USN Communications officer responsible for Iwo Jima flag image

Steven Zaloga, defense consultant

R. Timothy Ziemer, retired USN Admiral; former commander, Mid-Atlantic Region