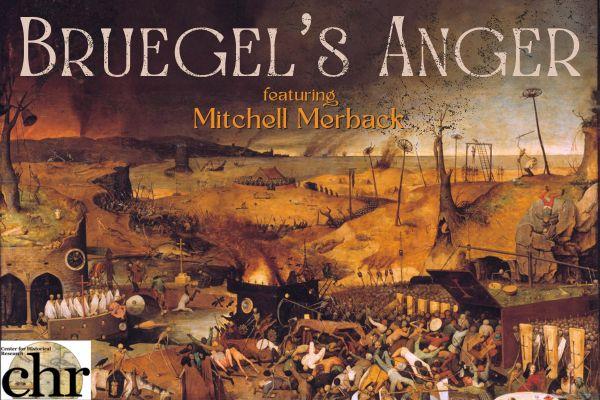

At the start of his career, Pieter Bruegel's anger (Ira) appears in allegorical guise, trodding a landscape cluttered with the follies, perversities, and monstrosities his reign on earth has unleashed. Capitalizing on the craze for works in the manner of Bosch, the engraving, part of a series of the Virtues and Vices, was no doubt a money-maker and a boon for the young Antwerp painter. But how much of Bruegel's own outlook on anger does it convey? With the exception of another early work, the personification of martial fury known as Dulle Griet (“Mad Meg”), anger practically disappears from Bruegel's oeuvre. Yet this absence deceives us if we regard anger only as moralizing subject. Anger remained a potent preoccupation in Bruegel's art, not as a social evil to be combatted but a passion of the soul in need of remedy. Bruegel's modern interpreters have sought the coordinates of his philosophical outlook in the humanist circle of Abraham Ortelius and its non-partisan Spiritualism, a worldly piety informed by Christian Stoicism. As the Low Countries erupted in religious factionalism, civic unrest, iconoclasm, and inquisitorial terror -- the time Bruegel's career was cresting -- consolation was sought in the works of Cicero and Seneca, who recommended the practice of philosophia to combat the deformations wrought by anger. Bruegel depicted the triumph of death over humanity, the shunning of Christ by Christians, and slaughter of the Bethlehem's innocents without a hint of anger. Was that attitude irenic, ironic, or medicinal?

Mitchell Merback is William Arnell and Everett Land Professor in Art History at Johns Hopkins University. His art-historical work centers on northern Europe during the Later Middle Ages, Early Modern and Reformation periods, with the arts of Germany, Austria, the Low Countries and France comprising the principal arena of investigation. His publications include: Perfection’s Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Durer’s Melencolia (Zone Books, 2017), Pilgrimage and Pogrom: Violence, Memory and Visual Culture of the Host-Miracle Shrines of Germany and Austria (University of Chicago Press, 2013), and Beyond the Yellow Badge: Anti-Judaism and Antisemitism in Medieval and Early Modern Visual Culture (Brill, 2008).

Cosponsored by the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, the Department of Art History, and the Department of Germanic Languages and Literature.