AS ONE OF Mexico’s most celebrated painters, Frida Kahlo mesmerizes, more than ever, young and old alike. Outside of museums and galleries in Mexico, the United States, Great Britain, and other parts of the world, thousands of eager fans impatiently jostle in long lines for the chance to visit exhibits of Kahlo’s small paintings and minute details of her existence. Once inside, spectators drift slowly from room to room, lingering in front of the glass cases that hold fragments of Kahlo’s dresses, body casts, shoes, jewelry, letters, and other assorted everyday items. And, of course, the gift shops conveniently located at the end of the various galleries provide the opportunity to buy all sorts of Kahlo memorabilia, including Kahlo’s image appearing on books, t-shirts, children’s dolls, pet clothing, jewelry, and an endless number of other items.

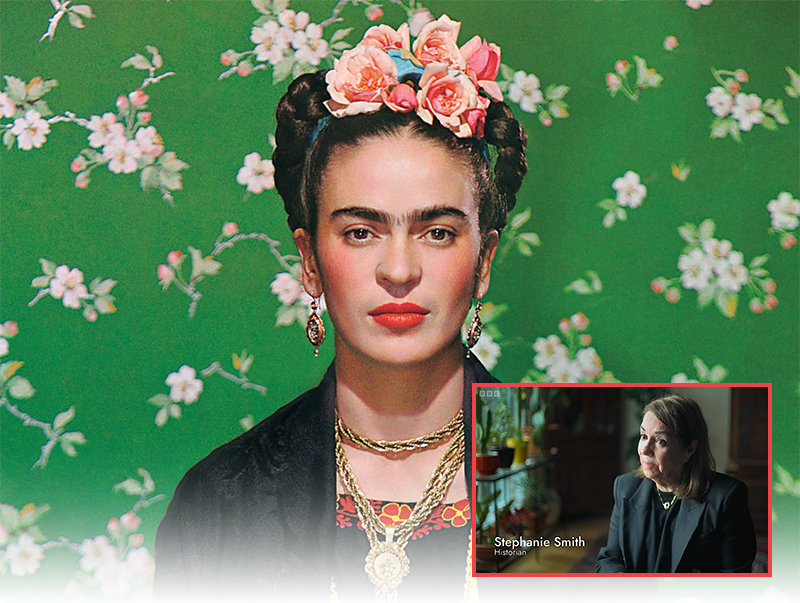

Why does Kahlo continue to captivate so many people years after her death in 1954? Professor Stephanie Smith’s new biography, Through Frida’s Eyes: Frida Kahlo, Politics, and the Creative Women Who Radicalized Mexico, seeks to answer this question by placing Kahlo fully into the rich and complex historical, cultural, and social contexts that shaped her unconventional life. Smith’s new work argues that at least part of the answer derives from viewers’ interpretations of Kahlo’s paintings and an almost reverential faith that her striking images provide a window into her life. Evoking their own personal emotions, both women and men alike empathize with Kahlo’s images that often depict the tragic details of her physical pain or devastating heartbreak caused by an unhappy marriage.

While periods of anguish contributed to Kahlo’s identity and art, Smith contends that narratives that focus primarily on her as the long-suffering woman diminish her revolutionary contributions and bury her historical memory beneath the rhetoric of a scorned lover limited by her broken body. Smith rewrites these traditional interpretations of Kahlo and instead analyzes her life and artistic contributions in novel ways as to stress her crucial contributions to Mexico’s radical political movements, her insistence on moving beyond the confines of the patriarchal constraints that defined postrevolutionary society, and her deep friendships with innovative women artists.

The Mexican Revolution dramatically shaped the world into which Kahlo first made her appearance as a tiny, boisterous baby in 1907. Born in Mexico City’s historically serene suburb of Coyoacán, Kahlo grew up surrounded by the ardent ideological movements and harsh physical destruction that radically impacted the country, principally from 1910 to 1917, but also well beyond. Kahlo came of age as an artist during the late 1920s and 1930s when transnational artists moved to Mexico City to experience the city’s exhilarating cultural environment. It was here that Kahlo not only befriended women artists and writers from Mexico and other countries, but in 1928 she also met the muralist Diego Rivera, whom she married in 1929. The couple moved back and forth between the U.S. and Mexico for the next few decades, although Kahlo’s health deteriorated rapidly. Throughout these years, she experienced a series of painful operations to correct the devastating damage originally caused by a 1925 trolley accident that shattered the young Kahlo’s body. Even in her poor physical state, Kahlo delighted in exhibiting her art in New York (1938) and Paris (1939), as well as her first one-person show in Mexico at the Galería Arte Contemporáneo during the spring of 1953. Sadly, Kahlo’s happiness with her exhibition was short-lived, as her doctors soon insisted on the amputation of Kahlo’s leg. Shattered, Kahlo nonetheless participated in her last public demonstration to protest the overthrow of Guatemala’s democratically elected president Jacobo Árbenz (1951-1954).

On July 13, 1954, Frida Kahlo died, and after a few hours Rivera transferred her gray coffin to the lobby of the prestigious Palacio de Bellas Artes. Just a few years later, in 1958, Mexico celebrated the inauguration of the Museo Frida Kahlo, located in the same Blue House in Coyoacán where Kahlo was born and died. Mexico’s beloved painter now became a true icon.

Smith has been interested in art and culture for many years. After earning her MFA, she lived as a professional artist for twelve years in New York City, where she actively participated in art shows and cultural events. In 2002, Smith earned her PhD in the history of Mexico; her interdisciplinary background provides a unique background from which to analyze the subject of art within a historical context.

Hoping to reach a broad audience, Smith’s study employs a lively, approachable style. By combining the readability of a narrative approach along with the deep, archival research supporting a historical monograph, Smith’s work is appropriate for scholars of Mexico, Latin America, and art history, but general readers also will appreciate—and enjoy—the book. Smith’s project utilizes extensive primary sources located in archives, libraries, and museums from five countries—Mexico, Holland, France, the United States, and Italy. Indicative of the excitement surrounding this new book on Kahlo, and the generosity of the families of some of Kahlo’s closest women friends, she also was given rare access to several personal and private archives that provide unique insight into Kahlo’s life and her friendships.

Representing Smith’s interest in reaching a large group of people, she recently appeared as a scholar and contributor in a new three-part BBC documentary, Becoming Frida Kahlo, which premiered in the U.K. on March 10, 2023. As a historian, she provided the context for Kahlo’s art and life, especially in Mexico, for parts one and three. ■

Written by Stephanie Smith, Professor of History

Photos courtesy of the BBC